In Ireland there is a saying, "you're a long time dead", which speaks for itself and is often used to justify not doing something considered a chore, or even better, to do something that would be considered frivolous or even reckless.

Another saying in Ireland is "the dust will be there long after you're gone" pointing to the ridiculous chore of trying to keep a permanently dust-free household.

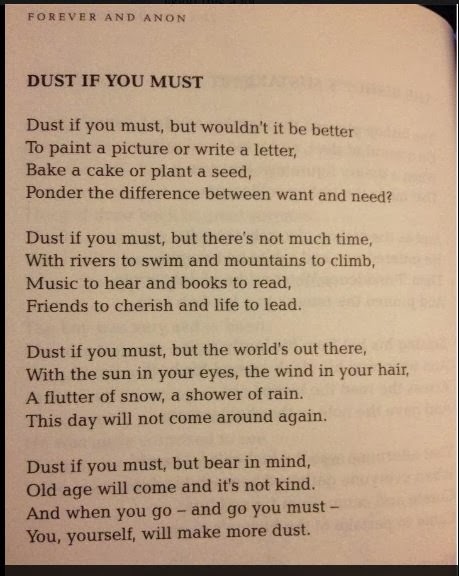

I found this poem which truly expands and enlightens the theme.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

I came across an old tradition that I had not heard of before when chatting to my father , aged 83 years, this evening. As a little boy in rural Ireland, he lived with his parents and an extended family of uncles, his mothers brothers, they kept a small farm and had a bee-hive for honey and wax. He spoke of the custom of telling the bees if someone in the household had died. He has memories of approaching the bees, saying to them "Uncle Tom is dead" and scampering quickly away.

I was left wondering about this and did some searching. I found that it was a well known folk lore in Bee Keeping tradition, which amused me as my father lived across the beach from a small fishing village in a small, and then Irish-only speaking, community.

The custom is steeped in respect for the Bees and what they bring to the household and it also speaks of mysticism and the relation that we have with nature. Sadly for many of us, where we have become disconnected with the land, we have lost the language to communicate with nature.

There must be more to this than meets the eye....

There must be more to this than meets the eye....

Telling the bees

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The telling of the bees is a traditional English custom, in which bees would be told of important events in their keeper's lives, such as births, marriages, or departures and returns in the household. The bees were most commonly told of deaths in their master's family. The custom was prevalent all over England, as well as in a few places in Ireland and Wales but not in Scotland.[1][2] If the custom was omitted or forgotten then it was believed a penalty would be paid, that the bees might leave their hive, stop producing honey, or die.[3]

To inform the bees of a death their hive might be hung with a black cloth, while a "doleful tune" is sung.[3] Another method of "telling the bees" would be for their master to approach the hive and knock gently upon it. The house key might also be used to knock on the hive.[1] When the master of the house had the attention of the bees they would tell the bees the name of the person that had died.[3]

Food and drink from a beekeeper's funeral would also be left by the hive for the bees, including the funeral biscuits and wine.[1] The hive would also be lifted a few inches and put down again at the same time as the coffin.[1] The hive might also be rotated to face the funeral procession, and draped with mourning cloth.[1] If a wedding occurred in the household, the hive might be decorated, and a slice of wedding cake left by their hive.[1][4][5] The decoration of hives appears to date to the early 19th century.[1]

The custom spread with European immigration to the United States in the 19th century.[4] An 1890 article in The Courier-Journal newspaper also described the practice of inviting bees to the funeral.[4]

The custom has given its name to poems by Deborah Digges, John Ennis, Eugene Field, Carol Frost and John Greenleaf Whittier.[6][7][8][9][10]

To inform the bees of a death their hive might be hung with a black cloth, while a "doleful tune" is sung.[3] Another method of "telling the bees" would be for their master to approach the hive and knock gently upon it. The house key might also be used to knock on the hive.[1] When the master of the house had the attention of the bees they would tell the bees the name of the person that had died.[3]

Food and drink from a beekeeper's funeral would also be left by the hive for the bees, including the funeral biscuits and wine.[1] The hive would also be lifted a few inches and put down again at the same time as the coffin.[1] The hive might also be rotated to face the funeral procession, and draped with mourning cloth.[1] If a wedding occurred in the household, the hive might be decorated, and a slice of wedding cake left by their hive.[1][4][5] The decoration of hives appears to date to the early 19th century.[1]

The custom spread with European immigration to the United States in the 19th century.[4] An 1890 article in The Courier-Journal newspaper also described the practice of inviting bees to the funeral.[4]

The custom has given its name to poems by Deborah Digges, John Ennis, Eugene Field, Carol Frost and John Greenleaf Whittier.[6][7][8][9][10]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Steve Roud (6 April 2006). The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland. Penguin Books Limited. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-14-194162-2.

- Jump up ^ Shakespeare's Greenwood. Ardent Media. p. 159. GGKEY:72QTHK377PC.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Samuel Adams Drake (1 January 2001). New England Legends and Folk Lore. Digital Scanning Inc. ISBN 978-1-58218-443-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tammy Horn (21 April 2006). Bees in America: How the Honey Bee Shaped a Nation. University Press of Kentucky. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8131-7206-4.

- Jump up ^ Michael O'Malley (4 November 2010). The Wisdom of Bees: What the Hive Can Teach Business about Leadership, Efficiency, and Growth. Penguin Books Limited. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-670-91949-9.

- Jump up ^ John Greenleaf Whittier (1975). The Letters of John Greenleaf Whittier. Harvard University Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-674-52830-7.

- Jump up ^ Carol Frost (30 May 2006). The Queen's Desertion: Poems. Northwestern University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8101-5176-5.

- Jump up ^ Eugene Field (March 2008). The Poems of Eugene Field. Wildside Press LLC. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-4344-6312-8.

- Jump up ^ Deborah Digges (2 April 2009). Trapeze. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-307-54821-4.

- Jump up ^ "John Ennis". Poetry International - John Ennis. Poetry International. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.