Today’s cities favour cars and commerce over kids

We treat kids like pests, but the real plague is our refusal to design cities in favour of people.

Here in Britain, there’s a company selling the Mosquito, a device designed to emit an unbearably high-pitched sound only kids can hear.

According to the website, the device is aimed at people ‘fed up with groups of kids damaging their property, hanging around in rowdy groups, littering, smoking and drinking, playing music and generally prevented from enjoying their home or business.’

“The Mosquito device is the only product on the market that has the teeth to bite back at these kids. The Mosquito alarm works not by being loud and painful, but by being UNBELIEVABLY annoying to the point where the kids CANNOT stay in the area being covered by the mosquito sound.”

Britain’s first children’s commissioner, Sir Al Aynsley-Green, described the device as “an ultrasonic weapon designed to stop kids gathering,” before adding that Britain was “one of the most child unfriendly countries in the world,” he said in 2010. The Mosquito is symptomatic of the way our cities are evolving to leave behind the most vulnerable.

Today’s increasingly homogenised urban areas favour cars and commerce over kids. Even pedestrianised areas are devoid of the public seating, loos and trees that encourage people to stop, talk and play. Pedestrianised areas are more likely to be windy corridors designed to corral shoppers to towards their next purchase.

It’s of vital importance because by 2050, around 70 per cent of people will be city dwellers. And the majority of them will be under 18. Today, over one billion children are growing up in cities.

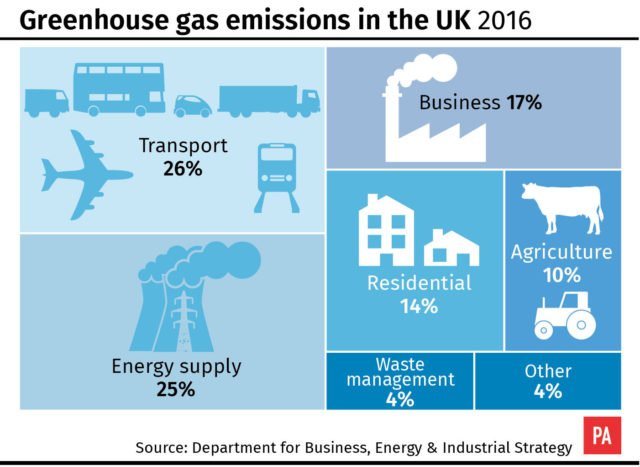

Creating a city that nurtures children instead of literally treating them like a pest is about more than provision of play areas. The air pollution and road danger caused by motorised traffic has a disproportionate effect on children. Furthermore, transport is now responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than any other source; our children will reap the effects of climate change to a greater extent than older generations.

Could our cities could become car free within a generation? The question may seem fanciful, but it is of critical importance to a metropolis like London if it is to control air pollution, encourage cycling and safeguard future generations.

Andrew Davis, managing director of the ETA, quotes our belief that the proliferation of cars comes with a wider social price. “Studies have found that people who live on a road with lots of traffic in an urban environment, have much more significant social problems over people who live in, for example, a cul-de-sac. The studies show that living on a main road is not good for your health. We know beyond reasonable doubt that motoring in towns and cities is actually damaging for our health in a much wider way than is recognised in the media generally.”

| “They’d actually think it was slightly mad to have a main road going through a centre of town”

“Take Denmark: there’s no town in Denmark which a main road goes through. No town. Zero. Here in Weybridge we’ve got an A road going through the town centre, and that simply wouldn’t happen in Denmark. They’d actually think it was slightly mad to have a main road going through a centre of town. They’ve been developing the concept over 30 years. Consequently, their culture is much happier than ours.”

“Cars damage our happiness in a way that we find very hard to understand directly, because they also help our happiness in our mobility. It’s that conundrum of having the mobility without the downside which is stretching us, I think, as a society.”

| “…a huge social cost of cutting off people who can’t drive…”

Dr Ian Walker, a specialist in traffic psychology at Bath University, adds to the argument: “One of the big social costs is the way it disenfranchises people who cannot or will not drive a car. Around 25% of British households do not have a car or access to one. How are they meant to get around when we plan shopping centres, facilities and amenities on the assumption you’re going to drive to them?”

There’s a huge social cost of cutting off people who can’t drive, and that particularly affects older people and children.